In this hillside town, topped by a medieval castle and surrounded by olive groves, the 120 municipal workers haven't been paid since May. Police have new orders not to use their patrol cars unless they get word of a traffic accident or a crime in progress.

The town pool is closed for the summer despite temperatures over 104 (40 Celsius) in the shade. Fees for the public day-care center have doubled. Water bills will soon go up 33 percent and local business owners are seething over euro9 million ($12.7 million) in unpaid bills owed by the town hall, much of it to them.

Spain's 8,115 municipalities are being hit by a crushing revenue hangover from a nearly two-decade building boom that went bust in 2008. Officials in Moratalla believe they are the first in Spain to publicly declare their town is on the verge of going broke — and that the only way out is an unprecedented program of drastically reducing services while boosting local taxes and fees in an austerity drive that could last eight years.

Moratalla and its mammoth debt "are the mirror image of a lot of towns" that have not yet fully admitted the extent of their dire financial circumstances, said Deputy Mayor Juan Soria. "These are hard measures, but they're necessary and I think we have to reinvent ourselves because we've lived beyond our means and we have to lower expectations."

There is growing concern in Spain that municipalities and regional governments are increasingly in danger of being unable to meet their obligations. Just this week in the region of Castilla la Mancha, not far from Moratalla, three out of every four pharmacies closed in a "strike" to protest late payment on euro125 million ($178.12 million) owed to them by the regional government for prescription drugs citizens get from Spain's regionally controlled national health care system.

Local and regional governments took on big obligations during Spain's boom years as their coffers swelled with revenue that has now dried up.

In many towns, employees were hired in droves as towns raked in cash from building permit fees, new business license fees and increasing property tax revenues. Officials went on a building boom of their own — constructing new roads, schools, day care centers, tourist attractions, parks and places for retirees to gather.

The 2008 financial crisis cut funding and turned the boom into a colossal bust. Now construction is at a standstill and businesses are closing as Spain grapples with unemployment of nearly 21 percent, a eurozone high. Many towns are struggling to meet payroll, can't fire workers because of public service employment rules, are frequently making late payments to the health care system and are trying to delay or restructure debt they took on for costly infrastructure projects.

The nation could be next in line for a bailout after Greece, Ireland and Portugal — and some in Moratalla say the example of their town shows Spain will need help from the European Union, despite pledges by federal officials that Spain won't need a bailout.

Debt held by Spanish local governments stood at euro35 billion at the end of 2010, up 11 percent from 2008, amid predictions the amount could go higher this year as municipal revenue continues to decline.

"The outlook is bad, and without addressing the problems of the municipalities we'll have more examples like Moratalla," said Pedro Arahuetes, Segovia's mayor and president of the finance commission for the association that represents Spain's municipalities and provinces. "It's either raise taxes or reduce services. There is no machine to make money."

Arahuetes says Spain's federal government must consider a controversial reform to mandate the mergers of small communities so they can band together to save on costs, at least for smaller towns numbering 400 people or fewer that have their own municipal governments.

"The territorial distribution of towns in Spain is totally unsustainable and someone has to address this problem in a serious way," he said.

Greece did just that last year, turning its 1,034 municipalities into 325 to streamline services and cut waste and expenditures. The program is aimed at saving euro1.2 billion a year, but this cornerstone of Greece's bailout reforms generated nationwide protests.

In debt-troubled Italy on Friday, Premier Silvio Berlusconi's government issued an emergency decree that would abolish the provincial administrations of towns with fewer than 300,000 people, while small towns with fewer than 1,000 residents would merge with larger communities. Berlusconi said that overall 54,000 elected positions in provincial, regional and city governments would be eliminated.

In Moratalla, population 8,500, Soria cringed at the idea of merging with a neighboring town, but said his community is functioning in constant crisis mode. Two weeks ago, Moratalla's two gas stations stopped filling the tanks of municipal vehicles when the owners lost all faith the town would ever pay euro120,000 ($170,000) in outstanding fuel bills.

"They have told us that they don't know when, how or even if they are going to be able to pay us," said Jose Antonio Martin, who owns one of the gas stations. He is convinced the town needs a bailout from the regional government of Murcia, though it has debt problems of its own.

Now municipal workers fill up at a local agricultural cooperative. But police barely use the cars anymore, doing most of their patrolling on foot. They simply don't go as much anymore to outlying areas where about 3,000 of the town's citizens live.

Officer Jose Antonio Navarro worries when he's walking around the pueblo, or town, that he won't be able to respond in time to a public safety emergency, and members of the force along with other town workers are struggling to make their mortgage payments because of the paycheck payment delays.

"It's a tough situation," he said. "Friends lend us money, and we go to our parents' homes to eat."

Townspeople are sick of constant bickering between local politicians over who's to blame for Moratalla's debt, and even how much it stands at. The ruling conservative Popular Party that won town hall in May elections says the debt load is euro29 million, while the local Socialist Party that previously held the mayor's post says it is euro16 million — and that their efforts to bring it down were stymied because they didn't have a majority on the city council.

Making matters even worse for Moratalla, its key rural tourism industry is hurting because of Europe's financial crisis, with the town attracting fewer Spaniards and foreigners to its narrow and winding streets leading up to the castle and pristine forest foot and bike paths in the shadow of steep mountains.

City Councilor Ana Victoria Rodriguez worries that recent Spanish media attention on Moratalla's financial problems could damage tourism even more.

"It gives the impression that this is a pueblo where they don't even pick up the trash," she said. "That's not true, but it's bad for tourism."

A riverside campsite with capacity for 800 people has about 300 staying there now at the height of the busy August period, way down from normal levels, said Amparo Llorente, president of the local merchant's association. And many come just come for the weekend, instead of staying for the two weeks they often took during Spain's economic boom.

Llorente, a newspaper stand owner, is owed euro2,000 by the town government for newspapers it used to buy for a retirement center and the local library. While the amount is a pittance compared with the town's other debts to merchants, Llorente says it's a lot for her small business, and that newspaper sales are down overall because townspeople have less money to spend.

While Moratalla may end up going broke or face years of tough times ahead, Llorente says the only good thing is that "we have had the courage to say it. There are many pueblos who haven't said it because they are hiding in the shadows."

She is one of the richest women in Spain, owns a dozen castles whose walls are hung with works by Goya, Velázquez and Titian and is a distant relative of King James II, Winston Churchill and Diana, Princess of Wales. Now, however, the 18th Duchess of Alba is giving away her immense personal fortune in order to be free to marry a minor civil servant.

She is one of the richest women in Spain, owns a dozen castles whose walls are hung with works by Goya, Velázquez and Titian and is a distant relative of King James II, Winston Churchill and Diana, Princess of Wales. Now, however, the 18th Duchess of Alba is giving away her immense personal fortune in order to be free to marry a minor civil servant. MAN has been branded "reckless" for taunting a bull with a pink umbrella before it gored him to death.

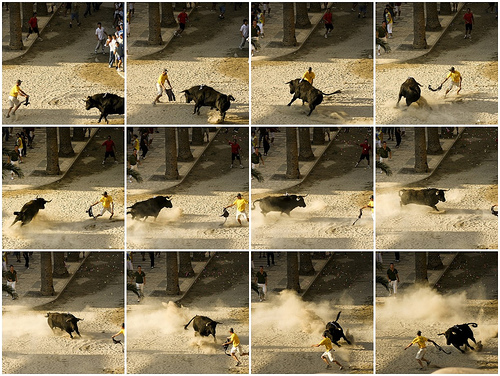

MAN has been branded "reckless" for taunting a bull with a pink umbrella before it gored him to death.